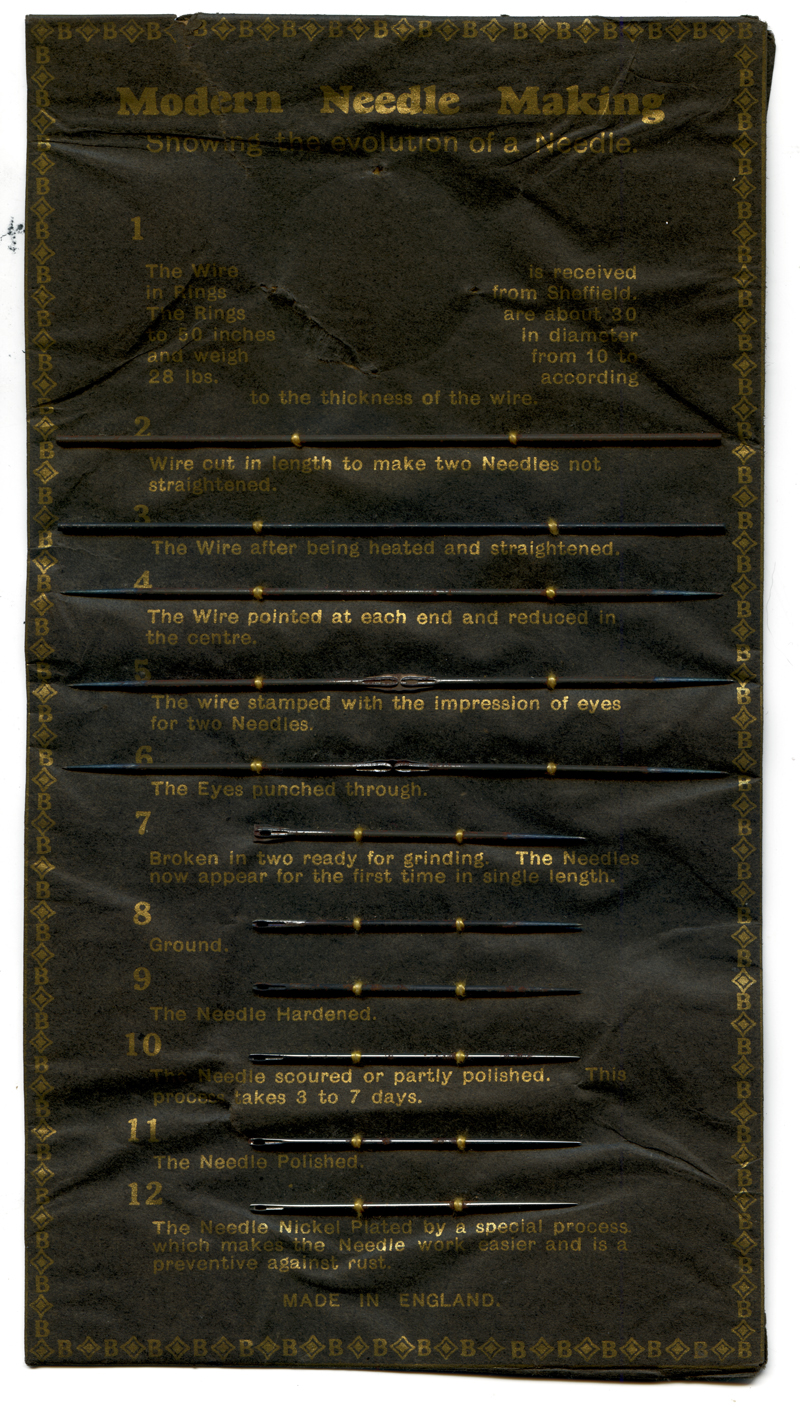

Top to bottom – removable crochet needle (G. Chambers 1847), crochet needle permanently mounted in handle (Milward Cleopatra), bone hook (Susan Bates), and steel one piece hook (Boye).

Do you call it a crochet hook but your great aunt Mabel calls it a crochet needle? Who’s right? Actually, both exist. The crochet tool used with thread to make lace in the 1840s was actually a needle mounted in a separate handle. One-man shops in Redditch, England, turned out crochet needles, sewing needles and fishing hooks. All were produced using the same materials and procedures. Today most crochet tools are formed with an integral handle and are called hooks.

Crochet needles from 1845 until about 1880 were made in the same manner and in the same facilities as sewing needles. Crochet needles have always been made of steel. But the steel manufacturing process was still as much of an art as a science in 1845. Steel is hard and brittle. It was difficult to work with the tools available in 1845. Steel needles were made of iron, which was much easier to work, and then the iron converted to steel. This way only a final polishing of the steel was needed. This method of converting iron to steel required that the items be small and thin.

Comparison of the 1847 G. Chambers crochet needle (bottom) with a modern sewing needle.

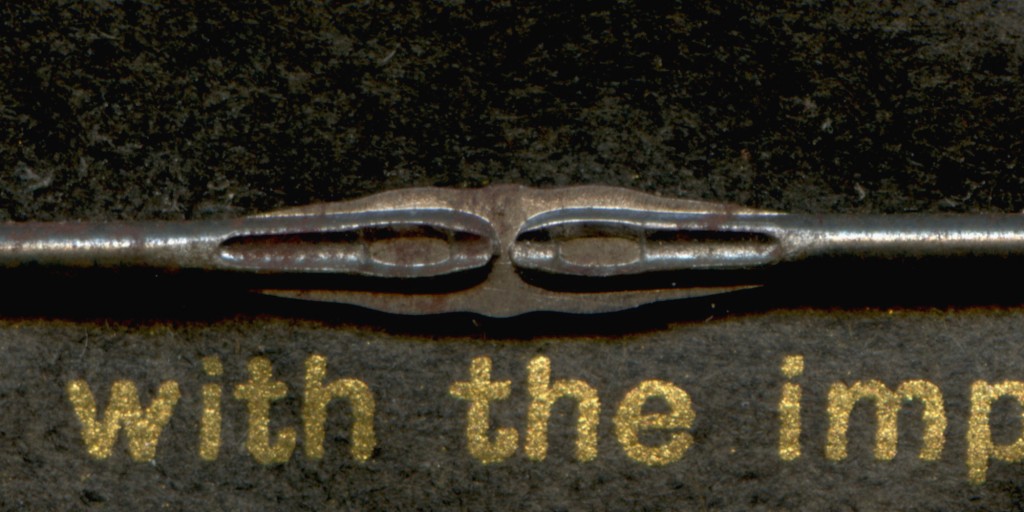

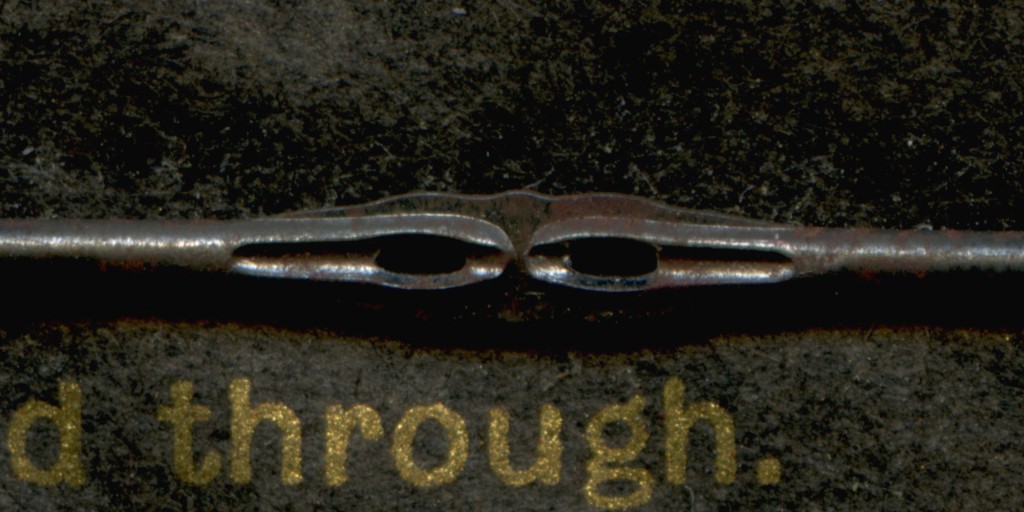

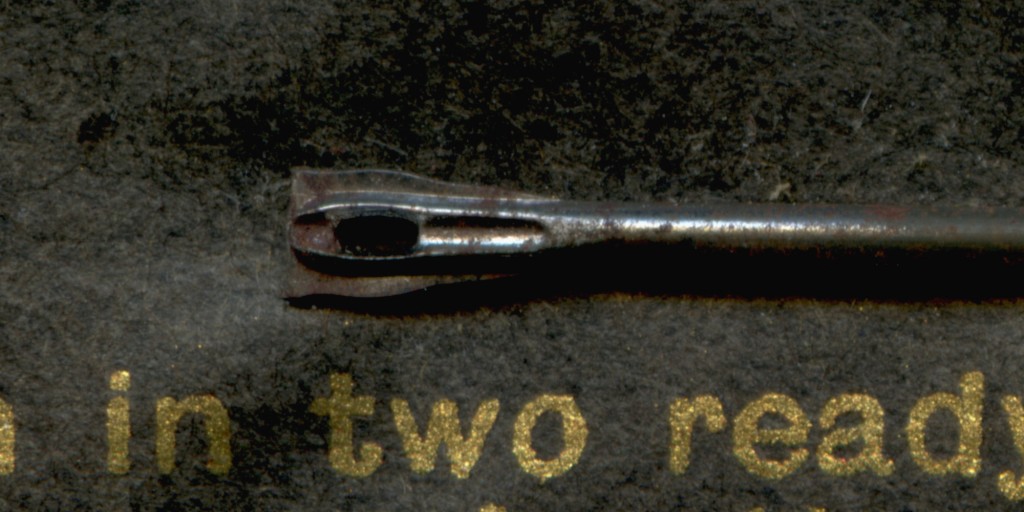

Needlemaking was a long, involved process. The needlemaker began with iron wire 0.072” in diameter. The wire was drawn to correct thickness, cut to length and straightened. Next the wire was stamped with the impression of the eye, two eyes being stamped back to back. Then the eye was punched through. Each different type of needle had it’s set of stamps and punches. For example, a tapestry needle has a large eye with a gutter (thread guide), a milliner’s needle has a small eye and no thread guide, and a crochet needle has a large eye with one side removed. The needle was pointed either before or after the eye was formed. In the case of some crochet needles, a point was not needed and for other crochet needles another eye was put on the opposite end to accommodate a chatelaine ring. The needles were then bound into large rolls with abrasive rocks and scoured until smooth.

These wrought iron needles were then converted to steel. A hole in the ground was lined with firebrick to form an oven. A fire was started in the hole and kept at white heat until the firebrick was white hot. A crucible containing alternate layers of needles and charcoal was placed in the hole and the temperature maintained for 24 hours. Then the crucible was allowed to cool, undisturbed for about 2 weeks. During the firing and cooling, the iron absorbed some of the carbon from the charcoal and the iron converted to low carbon steel. The needles became rough as they absorbed the carbon and had to be polished again. The harder steel needles required a longer scouring and polishing.

In 1856, the Bessemer process for making steel was patented which allowed large pieces of high quality steel to be made in large quantities. By 1880, all of the machinery and procedures needed to make steel hooks by swaging (stamping) were perfected. Crochet hook manufacture based on needlemaking methods was abandoned. It was now possible to make one piece steel crochet hooks from wires or rods large enough to be held in the hand without mounting in a separate handle. The steel hooks we buy new today are still made by swaging.