Nancy Nehring

Crochet Guild of America Chain Link annual conference

Manchester, New Hampshire, July 13, 2019

I am so pleased and honored to be added to the list of CGOA Hall of Famers – Jean Leinhauser, Margaret Hubert, Rita Weiss, Gwen Blakely-Kinsler, Lily Chin, Doris Chan, Carol Alexander, and Pauline Turner – each of whom I am privileged to know personally. Each of whom has worked many tireless years to promote crochet and CGOA.

I would like to thank the nominating committee for promoting my name, and the CGOA board and you, the members at large, for making my inclusion into the Hall of Fame possible.

In last year’s induction speech, Pauline Turner told us about her career as a needlework teacher and designer. I could do the same but it would cover much of the material that was in my 2005 CGOA Keynote Address. Instead, I will look forward and tell you about some of the crochet history projects that I am currently working on.

Gwen Blakley-Kinsler has told me, repeatedly, that my biggest contribution to CGOA is the work that I do as a crochet historian. My interest in crochet history extends beyond the small collection of favorite doilies from our grandmothers that we all have or pieces we’ve picked up at garage sales. I want to know so much more. I want to know when crochet started, who did it and what their lives were like, how did crochet develop through the years, where did the crochet hook come from, how have the hooks and threads changed over the years and how did that affect crochet styles.

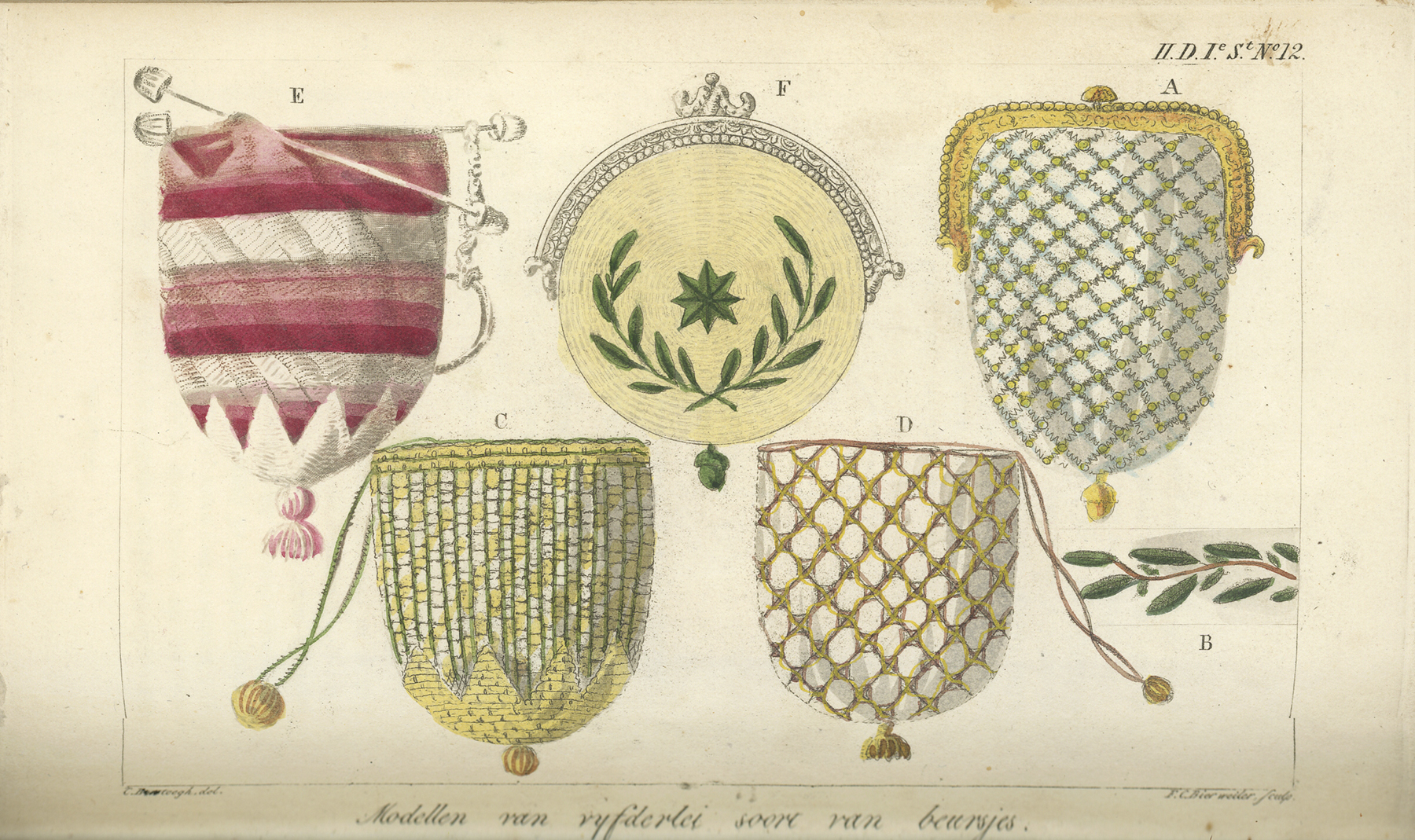

Like many of you, I want to know when and how crochet began. We know for certain crochet, with stitches taller than just slip stitch, existed by 1822. Pauline Turner can date the introduction of crochet to Ireland by the Ursuline nuns to that year and that introduction became the foundation of Irish crochet. The oldest published crochet patterns known are for silk purses in the 1823 issue of the Dutch magazine Penelope and illustrated in this plate.

But both of these events raise questions for further research. First, the Ursuline nuns were an order dedicated to educating girls and administering the poor. To teach the girls in their schools to crochet meant that the nuns thought that the girls could make money crocheting. That meant there had to be a commercial market for crochet already in existence in 1822. That market probably was in France supporting the Paris fashion industry.

Second, the Penelope article referred to the purses it was providing patterns for as being “in vogue”. But to be in vogue, very similar purses had to already exist for a least a couple of years. And they must have been crocheted. Penelope would have printed patterns in another technique if crochet wasn’t popular. In this plate from the magazine, the top 3 purses are crocheted, the bottom 2 use other techniques.

Fashion design in the 1800s wasn’t much different than it is today so let’s look at a modern example. For a crochet pattern to be in vogue usually means that it is a copy of a commercial product. Think of the crochet poncho that Martha Stewart wore when she left prison which is pictured here from the Lion Brand Martha Stewart Coming Home Poncho pattern by our own Doris Chan. Crochet patterns for the poncho were available almost overnight and very popular. So, were crocheted purses available commercially before the 1823 patterns? Likewise, Irish crochet was a commercial product sold to the rich before patterns aimed at the middle class were published. So my question is “Are we looking for the origins of crochet in the wrong place?” Should we be looking at commercial fashion not patterns for the middle class? Furthermore, should be we looking in continental Europe not England? England has been the area of focus based on the 1812 reference to slip stitch crochet in “Memoirs of a Highland Lady” and the flood of crochet patterns that came from Great Britain in the 1840s and 50s but perhaps the search should shift to non-English speaking countries. The Ursuline nuns came from France, Penelope was published in the Netherlands, and slip stitch crochet appears to have been more popular in the Scandinavian countries and continental Europe than in Great Britain.

Another area that I’m interested in is collecting old crochet hooks. I probably began collecting hooks in the 1980s. At first, I’d occasionally find an unusual hook at a local flea market or antique store. My collection grew slowly. Then came ebay … The more hooks I collected, the more questions I had. What did the earliest hooks look like? Who manufactured them? Can I date the old hooks? Could I collect all of the different names stamped on the flats of steel hooks? Surely I thought, some of the answers could be found in books on antique needlework tools. That was not the case. If I wanted to know anything about the history of crochet hooks, I was going to have to dig it out myself.

The first thing you have to do in crochet hook research is look at a lot of hooks. Then you can begin to group similar hooks together. And eventually you get a clue to a patent, a manufacturer, a location or other useful information. I’ve been digging for more than 30 years now. I have just recently completed the first cataloging of my crochet hook collection. This is important for 3 reasons. First, it required me to organize my hooks in a logic manner. I’m now ready to start writing the results of my research so it can be passed onto others. Second, this type of documentation or provenance is required for hook collections to be accepted by museums. Third, it’s required to value the collections.

I’ve been able to answer some of my questions about crochet hooks. Through patent searches, I can date my oldest crochet hook to 1847 and I’m pretty sure there are not older crochet hooks. I can date most steel crochet hooks to within 20 years of manufacture. This is an interdisciplinary effort based on changes in steel making technology, improvements in manufacturing techniques and machines, timing of sociopolitical events such as new laws and wars, etc. And about those imprints on the flats of steel hooks – I have hooks with about 125 unique names. This does not include familial names where the same name changes script styles or have other minor variations. I know I’m missing some but not very many.

Now, before you ask, the answer to the question everyone wants to know – How many crochet hooks do I have? When I actually got around to cataloging them all, I counted about 1500 in my main collection. Yes, you have to look at a lot of hooks.

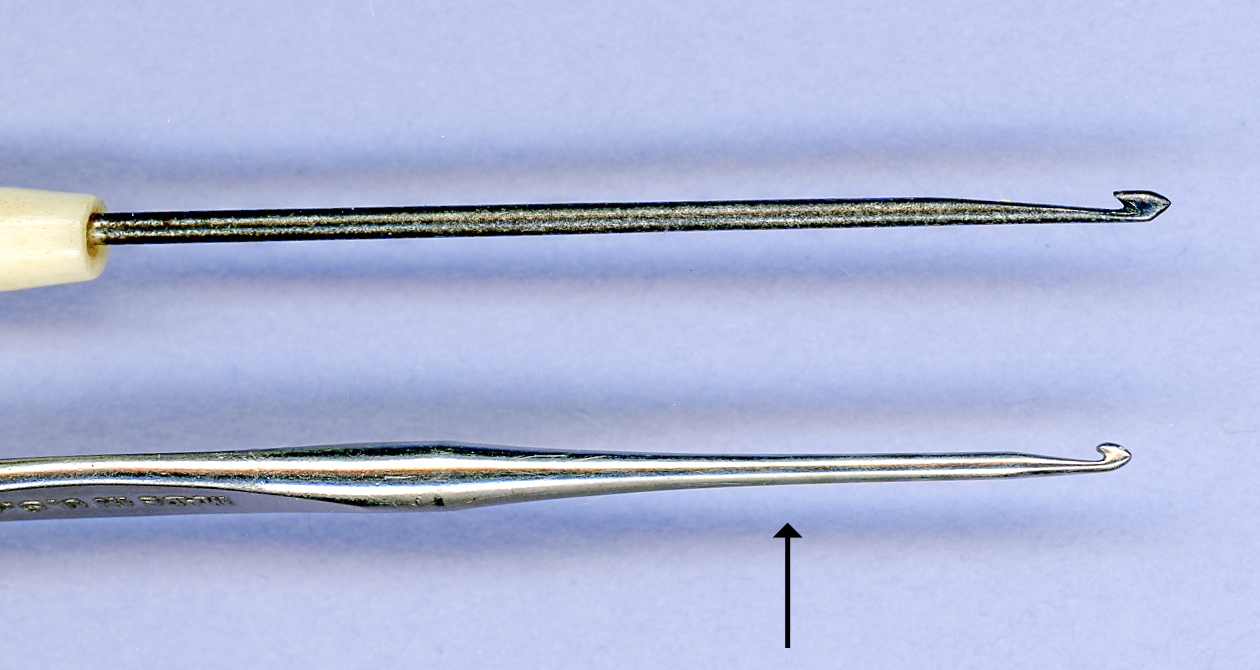

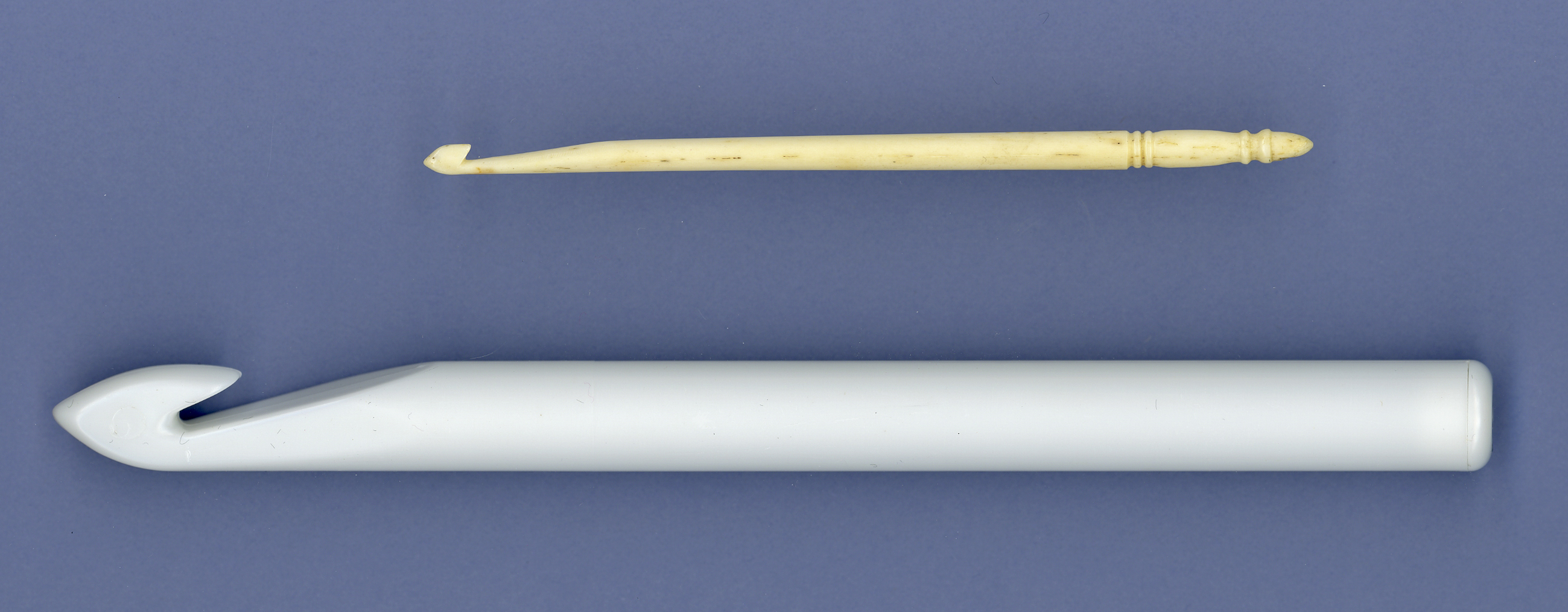

The materials and styles of crochet hooks have changed over time as have threads and yarns. Both affect how and what we crochet. Steel crochet hooks went from being made from wire to being made from rod as seen in the photo. Hooks for yarn went from ivory to bone to plastic. Both progressions changed the way we crochet.

Steel crochet hooks were originally made from wire using the same techniques as needlemaking. This resulted in a hook with a very long, even shank. By 1915, wire hooks had been completely replaced by stamped hooks made from steel rod where the shank gets fatter rapidly above the needle starting at the arrow in the photo.

My favorite example is the bullion stitch, featured in this 1890s reproduction button. The stitch requires multiple yarn overs and then one loop is pulled though all of the yarn overs at once. Up to 20 yarn overs might be used for a stitch. The result is a nice, tight, even stitch. A steel rod hook with its flaring shank produces a bullion stitch that is fan shaped, very wide at the top. The top of the fan may be so loose that the yarn overs can get caught and snag. The bullion stitch disappeared from patterns when rod hooks became the norm about 1915. I reintroduced the bullion stitch for making reproduction crochet buttons in 1996 but modern hooks limit the number of yarn overs to about 10.

We can see another change in style in yarn work. Before WW2, ivory or bone hooks were typically used for wool, bone being the more common. The hooks were rarely larger than a size H or 5mm. This was partly due to the limited size of cow leg bones used to make the hooks. Although plastics had been around since just before 1900, improvements in chemical technology during and after WW2 allowed plastics with customized properties. We crocheters benefited with more durable and lightweight crochet hooks. Chunky crochet using lightweight jumbo hooks was now possible.

Lastly, I’d like to tell you about my fascination with the people who crocheted. Who were they? What were their daily lives like? Crochet is not historically significant except perhaps Irish crochet during the potato famine. Crochet didn’t start wars or create commercial empires. It was women’s work done mostly in odd bits of time when daily chores were done, so it wasn’t considered worthy of documenting. All we have to show for this work are doilies and collars handed down as family heirlooms and an occasional sampler usually without benefit of maker’s name.

Our American view of social history over the last few decades has changed, expanding to be less Euro centric and to include more women and minority groups. Stories of women who crocheted that give insight into the lives of everyday people are now considered historically valuable. The stories I record may not be 100% accurate. They are usually told to me by relatives years, sometimes generations, after the crocheter has passed away. Genealogy work, census data, and newspaper clippings can correct some errors and flush out a story but even without that, the stories are entertaining.

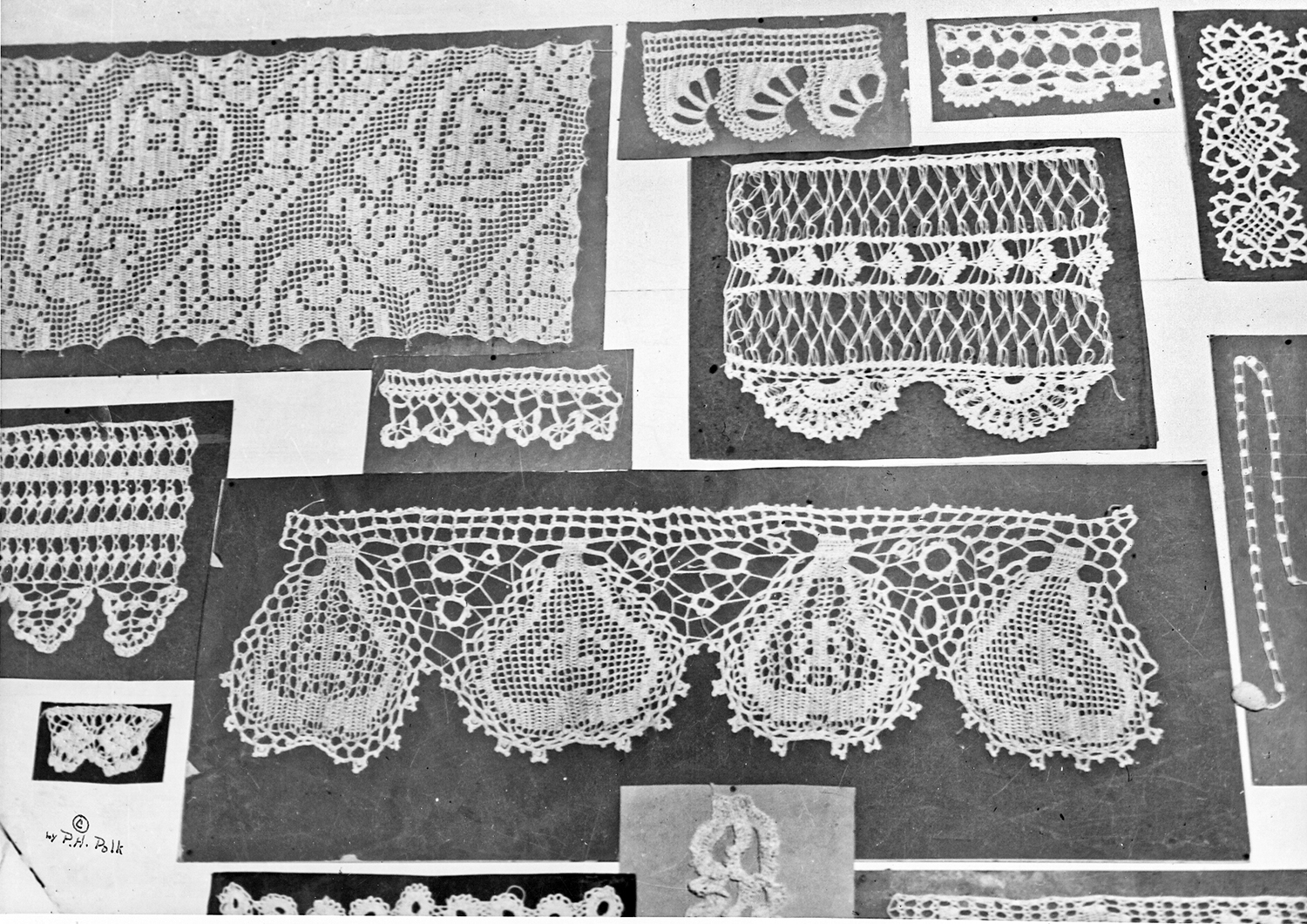

I wrote about Evdokia Gunn, pictured here with her daughter Helen, in a 2004 PieceWork magazine article after her granddaughter showed me a box full of swatches that Evdokia had made. In 1925 Evdokia was the young, pregnant wife of a White Russian officer during the Bolshevik Revolution. Serge was captured in China, returned to Orenberg, placed under house arrest and scheduled for execution. He arranged for Evdokia, with family jewels sewn into the hem of her skirt, to escape Russia by taking the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok and then a ship to Shanghai were there was a large White Russian community. Helen was born three days after she arrived in Shanghai. Evdokia remarried and after Helen left for boarding school in the 1930s Evdokia took a number of jobs to keep busy. One was sample maker for a Chinese textile company. Evdokia would crochet whole pieces like doilies, individual motifs for tablecloths or bedspreads, and swatches of edgings and insertions from 1920s and 30s European and American pattern books. Her samples were used by Chinese women who couldn’t read English to do production work for crochet destined for overseas markets.

I’m currently working on an article about the crochet of George Washington Carver. Carver was known professionally for his lifelong work in agriculture as a professor at Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University, in Alabama. Carver was also an excellent artist. One of his favorite hobbies was crochet which he learned as a child from his foster mother. Most of his finished crochet pieces were given away as gifts but he also had an extensive swatch collection which was displayed by the institute in 1940 as part of a Carver art exhibition. This is a photo from that exhibition. I’ve made trips to both Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site and George Washington Carver National Monument in Neosho, Missouri, to research and photograph his crochet.

And finally I’d tell you a story about one of my favorite people, my grandmother Laura Nehring.

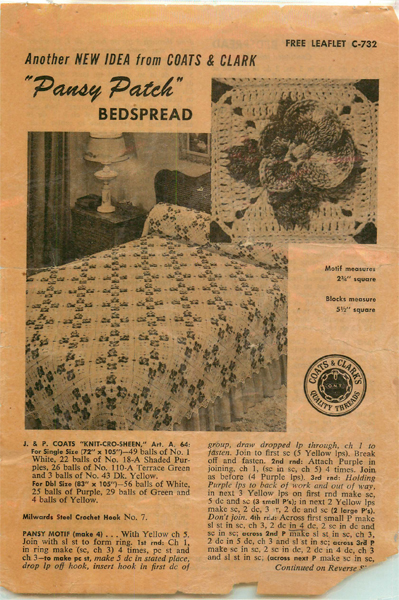

I remember as a child watching her crochet. One year she was making a pansy bedspread from a Coats and Clark leaflet. Every Saturday night I and my siblings would stay at her house while my parents went square dancing. For the first few weeks I watched as piles of purple and white variegated pansies grew on her old Singer treadle sewing machine cabinet that she used as a work table. And what little girl doesn’t love purple variegated thread. Then the piles of pansies shrank as stacks of white squares with pansy centers grew. Then came stacks of plain white squares. The stacks became so tall and numerous that the entire project got relegated to several large paper grocery bags piled in the corner. Then one week I was shocked to see that the bags were gone. Grandma told me to go look on her bed and there was her beautiful pansy bedspread.

Of all the crochet stories that can be told, these personal, first hand stories are the ones each of us cherish. They are the most personal, the most unique and the most accurate. They are the ones we most want to preserve. They are our history and our soul.